As it approaches its tenth year, our nation’s longest war is showing signs of waning. Meanwhile, our soldiers are falling apart.

From a series of portraits documenting the stress faced by Marines patrolling Afghanistan's Helmand Province. The men in these pictures have no known health problems themselves.(Photo: Louis Palu/Zuma Press)

Feb 6, 2011 - The first time I meet David Booth, a 39-year-old former medic and surgeon’s assistant who retired this past spring after nineteen years in the active Army Reserve, I make the awkward mistake of proposing we go out to lunch. It seems a natural suggestion. The weather is still warm, and he has told me to meet him in the lobby of his office downtown, so I assume he wants to go out, not back to his desk, when I show up around noon. But it turns out that in the six months he has been at his job, Booth has never left his office in the middle of the day, except to run across the street, and he is simply too polite to say so. From the moment we step outside, it’s clear how unusual this excursion is for him. As we walk, he hews close to the buildings on his right (“If a building’s to my right, no one is going to walk by me on my right”), and when we arrive at the restaurant, he quietly takes a seat at the table closest to the door, his back against the wall. His large brown eyes immediately start darting around.

“How’s your sleep?” I ask him.

“I don’t,” he answers.

Depending on the war, post-traumatic stress can have many expressions, but this war, because of its omnipresent suicide bombers and roadside explosives, seems to have disproportionately rendered its soldiers afraid of two things: driving and crowds. Movie theaters, subway cars, densely packed spaces—all can pose problems for soldiers, because marketplaces are frequent targets for explosions; so can any vehicle, because IEDs are this war’s lethal booby trap of choice. {continued}

Monday, February 14, 2011

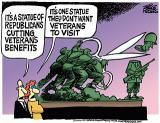

Why Our Returning Soldiers are Falling Apart

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment